Research Group on Global Issues #7

"Research Reports" are compiled by participants in research groups set up at the Japan Institute of International Affairs, and are designed to disseminate, in a timely fashion, the content of presentations made at research group meetings or analyses of current affairs. The "Research Reports" represent their authors' views. In addition to these "Research Reports", individual research groups will publish "Research Bulletins" covering the full range of the group's research themes.

Introduction

With the COVID-19 pandemic threatening the lives and livelihoods of all people on Earth, UN Secretary-General Guterres from the outset has called for more international solidarity and cooperation than ever to respond to the coronavirus. Today, after a quarter of a century since the concept of human security was first brought to the world by the UNDP in 1994, the pandemic struck just as the importance of reconsidering its value and implementation in light of changes within the international community was being debated. In 2020, discussions about rethinking the concept and practice of human security in the context of the coronavirus pandemic increased, especially among academic societies and aid workers in Japan.

This can be attributed to several factors. First, it is well known in the international community that Japan played a leading role in promoting the concept of human security as a new international norm. I believe that the greatest motivation of Japanese stakeholders is their keen awareness of their responsibility to deepen this concept as the backbone of international cooperation while continuing to adapt it to changes in the international community. Second, while the coronavirus pandemic has increased the importance of human security, which is centered on protecting people's lives, livelihoods and dignity, and aspiring to a world where "no one is left behind", we are faced with the reality that the world is not necessarily moving in that direction. While it has been pointed out that human rights, democracy and the dignity of individuals have been hidden behind the rhetoric of responding to COVID-19, and that relative interest in human security has been declining, Japan has a role to play in sounding the alarm about this situation and demonstrating the way of international cooperation that returns to the starting point of human security. Third, human security has a high affinity with the "Agenda for Sustainable Development 2030" adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015 and its specific "Sustainable Development Goals" (SDGs), and provides an approach ("protection and empowerment") for the promotion of SDGs. In connection with the second point as well, a way is suggested that Japan, when considering international contributions during and after the coronavirus era, should build up its track record in achieving SDGs through a human security approach and share its effectiveness with the rest of the international community.

From these three perspectives, this paper examines Japan's role centered on human security during and after the coronavirus era, particularly in terms of Official Development Assistance (ODA).

Human security and Japan: why Japan?

First, with regard to Japan's responsibility for deepening and promoting human security, I would like first to confirm Japan's position on human security. As noted above, Japan has been a strong promoter of human security in the international community, and this concept is positioned as the basic policy for ODA in the ODA Charter of 2003 and the Development Cooperation Charter of 2015.

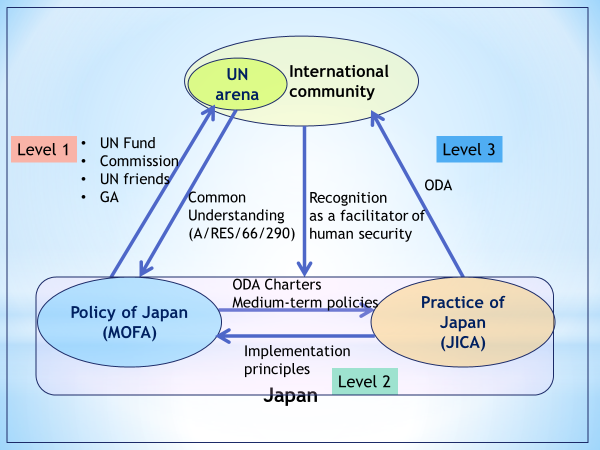

Figure 1 shows how Japan has promoted the concept of human security in the international community, reflected it in its ODA policy, and returned it to the international community.

Figure 1: Japan and human security

Source: Author

I see this process taking place at three levels. At Level 1, in relation to the Constitution, the Japanese government worked to establish the concept at the United Nations in order to make human security an agenda item for the international community that underpins international contributions in fields other than military affairs. In March 1999, the Japanese government made a contribution to establish the Trust Fund for Human Security at the United Nations. At the United Nations Millennium Summit in September 2000, Prime Minister Yoshiro Mori declared that human security would be the pillar of Japan's diplomacy, and in the following year he inaugurated the Commission on Human Security whose discussions were compiled in a report entitled Human Security Now in 2003 and submitted to the UN Secretary-General. The term "human security" itself first appeared in UN General Assembly resolutions in 2005, but at that point, it was limited to the General Assembly's intention to continue discussions on the definition. The Japanese government subsequently initiated the "Friends of Human Security" meetings, increased the number of countries and international organizations with an interest in human security, and developed a common understanding. These steady efforts bore fruit in the form of an eight-point common understanding incorporated into a resolution (A/RES/66/290) adopted by the UN General Assembly in September 2012. Since then, the Japanese government has continued to promote human security in the international arena. Special Advisor to the UN Secretary-General on Human Security Yukio Takasu is responsible for following up on the General Assembly's resolution; he is working closely with Member States, while in collaboration with UN-related agencies and other stakeholders, to promote the human security approach embodied in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the New York Declaration on Refugees and Migration, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, and the Sustainable Peace Agenda.

Level 2 shows domestic policy responses. Human security, which first emerged as a basic approach to ODA in the 1999 Medium-Term ODA Policy, was later upgraded to a basic policy in the 2003 ODA Charter, and its status is also reflected in the Development Cooperation Charter that was implemented in 2015. The formulation and implementation of these guidelines also reflect the points of view of practitioners, such as the implementation principles proposed by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), thereby creating a synergy between policy and practice. Based on the concept of human security, ODA has been implemented mainly through the Human Security Fund under the direct control of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Grant Assistance for Grassroots Human Security Projects, as well as through technical cooperation, loans and grant aid by JICA. This is shown at Level 3 in Figure 1. Today, the concept of human security has permeated not only ODA but also international cooperation by Japanese NGOs at the grassroots level, and it is an encouraging development that the number of people at the working level has increased.

It should also be noted that understanding of human security has gained traction with the general public. This means that while not everyone fully grasps the concept with the specific term of "human security", understanding of its ideals is widespread. The concept of human security, which was originally regarded as an international norm for foreign aid by some concerned parties, has gradually begun to be understood in the context of protecting lives, livelihoods and dignity in Japan since the Great East Japan Earthquake in March 2011. This indicates that the scope for protecting and promoting human security has expanded nationwide.

As described above, Japan, which has raised human security to an international concept and promoted the materialization of the concept through practice, has been seeking a new strategy based on the original sense of human security in response to threats that have expanded and changed over the past 25 years, long before the coronavirus pandemic. For example, in 2019, JICA adopted a new policy for strengthening its responses comprising digitalization, innovation and partnership. It also espoused new principles of action: (1) contribute to protecting people's "lives, livelihood and dignity"; (2) support the empowerment of people, organizations and societies so that people can pursue their own potential; and (3) contribute to the creation of societies resilient to diverse threats. In line with these policies and principles, assistance to address the coronavirus pandemic has begun.

Japan, which has led the promotion and deepening of human security, is aware of its responsibility as a flag-bearer in both policy and implementation in the context of COVID-19, and is now considering the role it will play in future.

Concept of "human security" to be reevaluated in light of COVID-19

Second, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the world is faced with the dilemma that, while the importance of human security centered on protecting people's lives, livelihoods and dignity and "leaving no one behind" is increasing, it is not necessarily moving in that direction. Japan has a significant role to play in this regard.

As of December 10, 2020, there were 68.89 million cases worldwide and more than 1.56 million deaths, according to Johns Hopkins University. Coronavirus is hitting developing countries as well as developed Western countries. For countries and regions in conflict, as well as nearly 80 million refugees, COVID-19 poses an additional threat to people's survival. COVID-19 has not only endangered health and life but has also caused economic stagnation. In particular, the socially vulnerable have suffered from growing disparities and increasing poverty. Faced with this reality, it is clear that international cooperation based on human security is urgently needed. For example, the COVAX Facility is at the forefront of international cooperation to support the supply of vaccines against the coronavirus.

On the other hand, there are countries that advocate the principle of putting their own states first in responding to the coronavirus, as well as countries that are willing to strengthen their government's authoritarian regime under the rhetoric of containment. On September 8, Xinhua reported that China had successfully ended the coronavirus pandemic ahead of any other country. According to the OECD Economic Outlook Interim Report released on September 16, China is the only G20 country expected to increase its GDP (by 1.8%) in 2020. Clearly, its response to the coronavirus through strong government control and surveillance appears to have been successful. However, what if the end result is a stronger state surveillance system and less freedom to live with dignity, in exchange for ensuring people's health and activating the economy? In addition, the United States (under the Trump administration), which places priority on its own, has so far turned its back on areas where international cooperation is indispensable, as seen in its withdrawal from the WHO and the Paris Agreement, and has also shown a negative attitude toward international cooperation on vaccines. These major powers seem to be undermining the three principles of human security - "freedom from fear" "freedom from poverty" and "freedom to live with dignity" - and turning their backs on the realization of a world in which "no one is left behind".

Under these contradictory circumstances, Japan may be able to reaffirm its own role. At a time when international cooperation based on the principle of human security is indispensable, the unique role Japan should play during and after the coronavirus pandemic, in distancing itself from the positions of these two major powers, is becoming increasingly important .

Japan's development assistance linking SDGs to human security

Third, the perspective of human security as an approach to achieving SDGs suggests a way for Japan to make progress on SDGs through a human security approach and share its effectiveness with the international community when considering international contributions during and after the coronavirus pandemic. As Professor Kanie points out in SDGs (Chuko Shinsho, 2020), if SDGs are regarded as "goal-based governance" and these goals are "directions to be pursued" for change and innovation, human security can play a role as an approach to achieving them. Efforts to achieve the SDGs with a high affinity for human security under the concept of "leaving no one behind" have become increasingly important, and a major direction of ODA is to work on the SDGs in keeping with the concept of "build back better". At a time when COVID-19 is placing a heavy burden on the socially vulnerable, the vision of a world in which "no one is left behind" is being received with a sense of realism. Specifically, while using the coronavirus response as an entry point, other threats stemming from the pandemic will need to be simultaneously addressed.

Next, the search for new partnerships, one of the SDGs, has begun amid the coronavirus pandemic. This latest pandemic has exposed the vulnerability of developed countries such as the United States and European nations, and the effectiveness of ODA, which has been modeled on developed countries, is being questioned by developing countries. On the other hand, African countries have performed well in the fight to protect people's lives and health at an early stage, thanks to the self-protection wisdom that people have learned from SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome), MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome), and the Ebola crisis. What we can take away from this experience are new ways of thinking about international cooperation and partnerships. ODA is beginning to shift towards exploring new social and economic systems by mobilizing the experience and wisdom of developing countries. In addition, as it became difficult for Japanese officials to travel to and from sites due to the coronavirus, they were forced to entrust their duties to local personnel. This has had positive results in developing capacities of local staff and empowering them. The coronavirus crisis is also being seen as an opportunity to undertake efforts to find new areas of cooperation. For example, the term "coronatech" refers to businesses that use so-called contactless technology, such as the introduction of remote diagnostics at medical sites and the development of apps that allow users to pay for minibuses using smartphones, as well as those that take advantage of coronavirus relief measures to manufacture masks and handwash-related goods. The number of such businesses is expected to grow particularly quickly in Africa.

Future prospects and challenges

Looking back on 2020, which was affected from start to finish by the coronavirus, we all realize that, in the long run, it is essential that we not rely solely on governments and international organizations but also enhance our own ability to protect ourselves by learning from experience and engaging in self-help efforts and mutual assistance in order to ensure that no one is left behind and that the lives, livelihoods, and dignity of people are protected. For Japan to continue to contribute to the achievement of SDGs through a human security approach, it is important to accumulate know-how on capacity building and empowerment of people, which remain issues in human security, and share it with the world. In the "Implementation of Human Security in East Asia" project conducted by JICA's Ogata Research Institute, it was found that the importance of human empowerment gradually increased during recovery phase, although protection by the government and international organizations was indispensable in an emergency. The author assumes that this empowerment will be considered on a case-by-case basis in the process of recovering from the coronavirus pandemic, but thinks that it may be possible to extract some common denominator (e.g., trust between local communities and governments/external donors). If this can be visualized, it is expected that understanding of self-help efforts, which is the essence of Japanese assistance, will spread around the world through the concept of human security.

It goes without saying that Japan's ability to continue taking the lead in human security during and after the coronavirus pandemic depends on demonstrating this in pursuing international cooperation and in addressing domestic issues.

This is English translation of Japanese paper originally published on January 29, 2021.