No. 312

- Strong domestic legal frameworks enhance a country's comparative advantage in contract-intensive industries with complex supply chains. This logic extends to the realm of economic security, suggesting that transparent governance and legal predictability attract investment in "economic security-intensive" industries, shaping the global supply chain configuration for strategic products with sensitive technologies.

- Securing supply chains for strategic products should move beyond government subsidies toward institutional development, particularly in legal frameworks, cybersecurity, and economic intelligence. The importance of businesses recognizing economic security as a core aspect of risk management is emphasized.

- To enhance competitiveness in economic security-intensive industries, Japan faces three key challenges: strengthening cybersecurity, increasing economic security awareness among SMEs, and advancing international regulatory cooperation. Uncertainty in global governance has intensified following the inauguration of the new US administration, further underscoring Japan's leadership role in upholding a rules-based economic order.

A Comparative Advantage in Economic Security

The relationship between institutions and the economy has been the subject of extensive research. Among the scholars contributing to this discourse, Professor Nathan Nunn of the University of British Columbia highlighted the connection between domestic institutions and a country's comparative advantage in international trade.

In classical trade theory, countries with an abundant labor force are considered to have a comparative advantage in producing labor-intensive products such as textiles, while countries with a rich capital endowment have a comparative advantage in capital-intensive products such as automobiles. Traditionally, products have been classified into these two categories based on the intensity of production factors.

However, Nunn (2007) suggests that products manufactured through complex supply chains involve various transactions that make them "contract-intensive," as exemplified by car engines, compressors, and photographic equipment. Just as countries with an abundant labor force enjoy a comparative advantage in labor-intensive industries, the quality of a country's domestic legal system significantly affects its international competitiveness in contract-intensive production.

By the same logic, countries with proper legal frameworks for intellectual property protection are likely to hold a comparative advantage in knowledge-intensive industries. Similarly, the presence of robust environmental and labor standards may serve as a source of competitiveness for suppliers of raw materials and manufacturing components, especially as the notion of corporate social responsibility gains increasing global attention.

This perspective can be extended to the domain of economic security:

- products incorporating sensitive technologies or critical strategic materials can be considered "economic security-intensive", and

- countries with well-developed legal frameworks and technological ecosystems relevant to economic security will hold a comparative advantage in economic security-intensive industries.

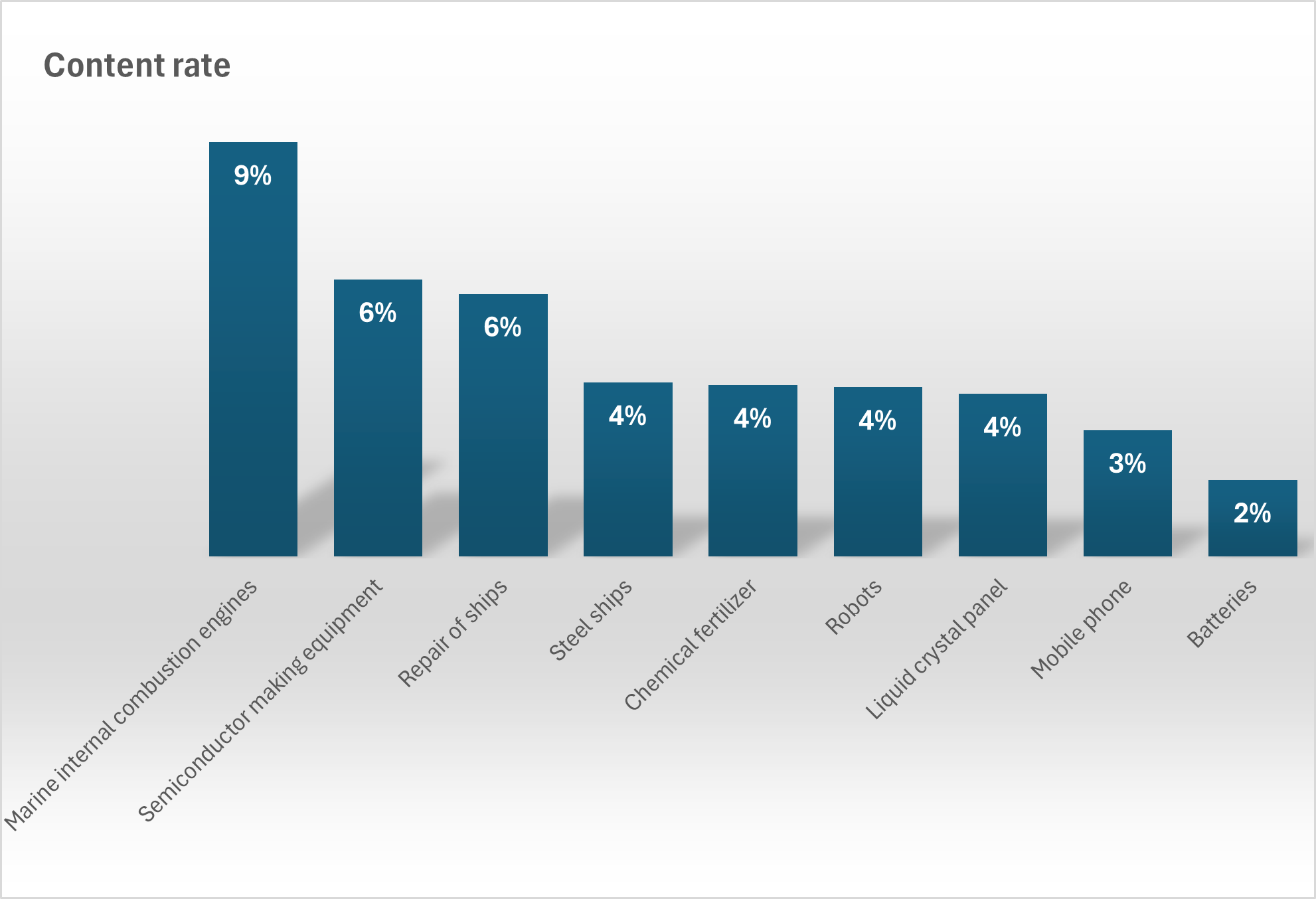

Figure 1: Japan's Economic Security-Intensive Products: 2020

Source: Author's calculations from Japan's 2020 input-output table

Note: The vertical axis presents each product's content rate (%) of Specified Critical Materials (designated by the Economic Security Promotion Act) that are identifiable in the sector classification of input-output tables. These are very preliminary estimates for illustrative purposes.

For multinational corporations, the predictability of the business environment is a crucial factor in determining the scale and direction of investments. As arbitrary government interventions in business and their political instrumentalization become increasingly common, transparent and robust legal foundations for economic security enhance business predictability, making investment in countries with well-established institutions more attractive.

For instance, dual-use products with both military and civilian applications--such as drones, which play a decisive role in modern warfare as well as in daily last-mile delivery services--highlight the importance of clear regulations. By incorporating extensive and detailed reference systems for regulated products within domestic legal frameworks, governments can reduce ambiguities in these technological gray zones and help firms manage their sensitive technology supply chains.

Just as labor-intensive industries once concentrated in China due to its vast labor pool, supply chains involving strategic products and sensitive technologies are likely to gravitate toward countries with institutional advantages in economic security.

Policy Implications--Still Bothering with Subsidies?

The policy implications of this argument are clear. Securing supply chains for strategic materials--a core element of economic security--should not rely solely on subsidy-based incentives. Instead, it should be advanced by strengthening the country's institutional foundations for economic security, e.g., developing domestic legal frameworks, improving cybersecurity, and enhancing economic intelligence through public-private cooperation.

Japan has made notable strides in this regard. In May 2024, a security clearance system was introduced in alignment with the legal backbone of the Economic Security Promotion Act.1 In contrast, the United States has yet to establish a comprehensive economic security framework, while European Union member states are still in the process of aligning their domestic laws with the overarching strategy announced in 2023. Japan thus leads in building relevant institutional frameworks, significantly enhancing its comparative advantage in economic security.

There are two preconditions for institutional advantages to function in the realm of economic security. First, geoeconomic risks must be tangible and increasing. Institutional robustness becomes particularly valuable in environments where arbitrary government interventions or economic coercion are prevalent. Second, geoeconomic risks must be properly recognized by business leaders, shareholders, and policymakers. Supply chains cannot be restructured effectively unless decision-makers fully acknowledge the risks at hand.

It is crucial for firms to realize that engagement with economic security is now a matter of risk management. When the issue of economic security was not widely understood, regulatory frameworks such as Japan's Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act were primarily perceived as compliance requirements imposed by authorities. In such circumstances, subsidy incentives may have been necessary to provide the initial momentum for supply chain restructuring.

However, government interventions through subsidies rely on public funds, which are not necessarily guaranteed in national budgets on a regular basis. Furthermore, they risk escalating into subsidy competitions among countries to secure critical supply chains. Instead of engaging in such an unproductive economic war of attrition, governments should prioritize building transparent institutional foundations that help firms prepare for and respond to geoeconomic risks based on their own calculi.

Impact on developing countries

The current argument also carries important implications for the growth strategies of developing countries. Until recently, the expansion of global value chains was largely propelled by cross-border capital flows in pursuit of low-cost labor. Many labor-abundant developing economies capitalized on this trend and achieved remarkable economic growth.

However, with the rapid advancement of information and communication technologies, industrial automation--especially through the use of robotics--has become increasingly prevalent in advanced economies. This technological shift has diminished the appeal of cheap overseas labor. As a result, export-oriented growth strategies centered on labor-intensive manufacturing, exemplified by China in the early stages of globalization, may no longer be regarded as a viable pathway. Today's developing countries must identify and cultivate alternative sources of competitiveness to position themselves effectively in the global economy.

Institutional reform, particularly in the direction of regulatory convergence with advanced economies, offers a promising alternative. For developing countries with a sufficient manufacturing base, the presence of robust domestic institutions is a critical prerequisite for integration into the global technological ecosystems. This is particularly true in supply chains involving semiconductors, advanced materials and other sensitive technologies. Efforts to join high-standard trade agreements such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) can serve as credible signals of a country's commitment to regulatory alignment.

Japan's Immediate Challenges

Given this policy landscape, what are the most pressing challenges for Japan?

First, Japan is widely perceived as lagging behind major Western countries in cybersecurity. Although the Basic Act on Cybersecurity was enacted in 2014 and has been revised multiple times since then, both the public and private sectors continue to exhibit slow progress in the development of crisis awareness, concrete countermeasures, and relevant personnel.

In February 2025, the Japanese government drafted legislation on proactive cyber defense. If enacted, this measure must be accompanied by systematic institutional design and adequate resource allocation to enhance national cybersecurity while maintaining constitutional safeguards for communication secrecy.

Second, extensive institutional commitments must be made in public-private partnerships to foster greater awareness of economic security, especially among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Many SMEs are not sufficiently aware of how their technologies and products are linked to national security or where critical information leakage may occur. While many large firms have already created specialized departments dedicated to economic security, SMEs by contrast often face financial and personnel constraints that hinder proactive engagement. In some cases, there is a fundamental lack of recognition of the risks of technology leakage. Addressing this issue requires comprehensive and sustained awareness-raising efforts by the government or lead firms in supply chains.

Finally, international cooperation for institutional development must be promoted. Expanding the number of countries that share common regulatory frameworks will increase firms' options for supply chain diversification to enhance resilience. Initiatives such as the US-EU Trade and Technology Council (TTC) and the supply chain agreement under the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) may serve this purpose.

However, this approach faces increasing uncertainty. There is growing concern that the new US administration may accelerate its inward-looking policy shift, withdrawing further from cooperative platforms that have been developed to date. Such a shift could trigger zero-sum competitions among countries, including subsidy races and tariff wars, making it increasingly difficult to maintain robust global governance through coordinated institutional arrangements.

At this critical juncture, Japan's leadership in upholding a rules-based international order will play a pivotal role in shaping the future of the global economy. While WTO reform must continue to receive sustained attention, Japan should place strategic emphasis on advancing the CPTPP to achieve high-level regulatory convergence, both in terms of extensive margin (by expanding membership) and intensive margin (through deeper regulatory hormonization among members).

The contents of this commentary are based on the author's article published in "Keizai-kyoshitsu", Nihon Keizai Shimbun, December 6, 2024.

Satoshi Inomata is a chief senior researcher of the Institute of Developing Economies, JETRO (IDE-JETRO).

Reference:

Nunn, N. 2007. "Relationship-Specificity, Incomplete Contracts, and the Pattern of Trade." Quarterly Journal of Economics 122 (2): 569-600.

1 The official name is the Act on the Promotion of Ensuring National Security through Integrated Implementation of Economic Measures.