JIIA Strategic Comments (2021-08)

Papers in the "JIIA Strategic Commentary Series" are prepared mainly by JIIA research fellows to provide commentary and policy-oriented analyses on significant international affairs issues in a readily comprehensible and timely manner.

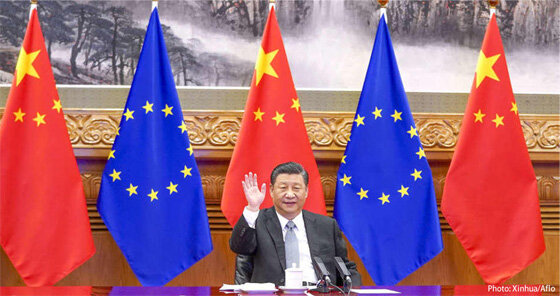

On March 22, 2021, the EU Foreign Affairs Council adopted sanctions on Chinese officials for human rights violations against the Uyghur minority in China. This was the first time in 30 years since the Tiananmen incident in 1989 that Europe had imposed sanctions on China. China immediately responded by calling the sanctions "interference in its internal affairs". While Sino-US relations remain difficult, China's relations with Europe have also become increasingly strained.

In Central and Eastern Europe, the '17+1' economic cooperation framework that China has promoted in recent years is turning a corner. There is widespread disappointment that the investments promised by China have not always been delivered. In this article, I would like to summarise the recent structure and problems of China-Europe relations, focusing on the dilemmas between economics and human rights, and consider the current situation of the 17+1.

Dilemmas between economics and human rights

Freedom, democracy and human rights are the core principles that underpin European societies. Most European countries have become stable democracies, although some, such as Hungary, have become increasingly authoritarian. China, on the other hand, is an authoritarian state where the Chinese Communist Party maintains a strong one-party dictatorship. In response to the Tiananmen incident in 1989, sanctions were imposed on China, forcing it into isolation from the international community. Even after the sanctions were lifted, China's human rights situation continued to be the subject of European criticism, and European condemnation of China over the human rights situation in Tibet prior to the 2008 Beijing Olympics also attracted widespread attention.

However, the relationship between China and Europe has not always been confrontational. In 1998, China and the EU regarded their ties as a "comprehensive partnership", which was upgraded to a "comprehensive strategic partnership" in 2003. Various frameworks for dialogue between China and the EU have been set up, and at one time it was even said that China and the EU had a honeymoon relationship. Dialogue between individual countries and China also took place frequently. In particular, the United Kingdom and Germany valued their respective bilateral relations with China, and promoted them through frequent visits and summit meetings following the establishment of Xi Jinping administration. In 2015, British Prime Minister David Cameron and Xi Jinping went to a pub and had an awkward chat, which left a strong impression on many people.

Needless to say, it is China's growing economy that brings Europe and China together. The EU is China's largest trading partner, and China is the EU's second largest trading partner after the US. Even though the pace of China's economic growth is slowing, it is still one of the fastest growing economies in the world and is already the second largest economy. China and Europe have become indispensable partners, at least in economic terms.

From China's point of view, this economic relationship is the stabiliser of its relations with Europe and the biggest card it can play. China is well aware that no matter how much Europe criticises China on human rights issues, its economy cannot survive without China. In the aftermath of the Tiananmen Incident, sanctions against China were lifted one way or the other in the end, with Japan serving as a breakthrough. In 2008, when the West stepped up its criticism of China over the Tibet issue, European countries did not boycott the Beijing Olympics and the issue was dropped. China itself had not changed in the process. It is natural for China to think that European countries will try to improve their relations with China again when the criticism from Europe about Hong Kong's version of the National Security Law in 2020 and the human rights violations against Uyghurs in Xinjiang cools down. From China's point of view, human rights diplomacy is in the first place a response to domestic public opinion in individual countries, lacking in effectiveness and little more than a symbolic performance.

Within Europe, there is a lack of alignment on the issue of relations with China. Germany has consistently tried to avoid a deterioration in relations with China by striking a balance between economics and human rights. Italy, for its part, has further deepened its relationship with China by officially joining the "Belt and Road Initiative", which is synonymous with Xi Jinping. From China's point of view, there is a recognition that while it may be possible to adopt symbolic sanctions in the EU arena, it is difficult to unite against China. It is worth noting, however, that in September the European Parliament adopted a report on "a new EU-China Strategy" that clearly toughened EU policy towards China. This may not necessarily be reflected in the policies of individual EU countries towards China and does not mean that Europe is currently united in its opposition to China, but it is certainly a reflection of the present state of Europe's overall view of China. It is also important to note that AUKUS was launched in September by Australia, the UK and the US. This framework is clearly China in mind, and China reacted strongly. What kind of policy the UK will adopt towards China after leaving the EU will be a major variable in the relationship between China and Europe.

The '17+1' at a turning point

In 2012, China launched the so-called '16+1' economic cooperation framework with Central and Eastern European countries (which later became the 17+1 with the addition of Greece), and has been holding annual summits. Central and Eastern Europe is an important region for China as it is on the route of the Belt and Road Initiative and is also a bridgehead to Western Europe. China has pledged to invest in Central and Eastern Europe and has continued to increase its presence there. However, at the summit meeting held online in February 2021, the Baltic States, Romania and Bulgaria did not attend at the head of state/government level, and later in June, Lithuania announced its withdrawal from the 17+1.

From the outset, there were concerns that the framework for cooperation between China and Central and Eastern Europe would lead to a fragmentation of Europe. However, China's economic power was attractive for Central and Eastern European counties which were in severe economic difficulties. As the 17+1 enters its tenth year, the economic benefits have not been as great as the Central and Eastern European countries had hoped. The intensifying confrontation between the US and China and the imposition of sanctions by the EU on China have forced Central and Eastern European countries to reconsider their relations with China.

There is also a clear division among the countries in Central and Eastern Europe. China has always attached great importance to the 17+1 framework, in that the Western European powers cannot get involved and China inevitably takes on a leading role. However, 12 of the 17 countries are members of the EU, and Lithuania, which has declared its withdrawal from the 17+1, argues that the EU should unite and move to a 27+1 framework, a stance understandably underpinned by concerns that a 17+1 framework would undermine the EU's east-west solidarity. However, Lithuania's actions have not necessarily led to break the 17+1 framework. The five Western Balkan states are not members of the EU in the first place, and some EU member states such as Hungary continue to have strong expectations of China. The 17+1 meeting in 2021 was notable for the absence of five heads of state/government, but on the flip side, 12 countries (including seven EU members) still see values in having their leaders participate in the framework. In particular, the EU and Western European countries' support for Central and Eastern European countries in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic has been inadequate, and the latter thus sought Chinese assistance. President Vucic of Serbia even welcomed the arrival of vaccines from China at the airport. China also remains strongly motivated to maintain the framework for cooperation with Central and Eastern European countries, a vital part of the Belt and Road Initiative.

The 17+1 (now 16+1) framework has reached a turning point, but it has not become entirely ineffective. China itself is modifying its investment and business development in Europe and is beginning to show a greater focus on quality. More than ever, Central and Eastern European countries need to be smart enough to secure their own interests while weighing up the balance among China, Western Europe, the US and other major powers.